The following six essays feature in the publications

MARJORIE COLEMAN – Finale, 2024

MARJORIE COLEMAN – The Last Hurrah, 2022

MARJORIE COLEMAN – Lyrical Stitch, 2020 and

MARJORIE COLEMAN – Following the Thread, 2019

Denouement – Wendy Lugg

I have had the privilege of writing essays in three previous publications documenting Marjorie Coleman’s life and work. Those essays, and Marjorie’s prodigious body of work comprising over 200 stitched textiles, can be viewed at the beautifully crafted website that I urge you to visit, marjoriecoleman.com

Marjorie’s most recent publication, The Last Hurrah, comprised works made in 2021 and 2022. Then aged 94, with failing health and unsteady fingers, she thought she had stitched her last piece and I was asked to write a postscript. Having already seen multiple versions of Marjorie’s “final piece” I knew there were more to come.

So I should not be surprised to be writing again in 2024. This current contribution must I suppose be an epilogue, a postscript to that postscript. Rather than repeat myself, I approach these words as a more personal tribute to my friend and mentor of forty years.

For the last two decades Marjorie and I have been part of a small group of long-time friends and makers who regularly come together to share our work and ideas. Marjorie, although a generation older than the rest of us, has kept us on our toes with her inquiring mind and the astounding variety of her abundant, dynamic creations.

Two years ago Marjorie declared that her hands were shaky and her imagination was tired. Yet these last works are vibrant evidence that the limitations of age and ill-health cannot deny a creative mind. Marjorie may be tiny in stature but she is mighty in spirit.

Asked to describe the intention behind individual pieces this latest body of work Marjorie is impatient, disinterested in offering any words beyond the titles stitched into their surface. They simply exist, flowing from her thoughts and hands.

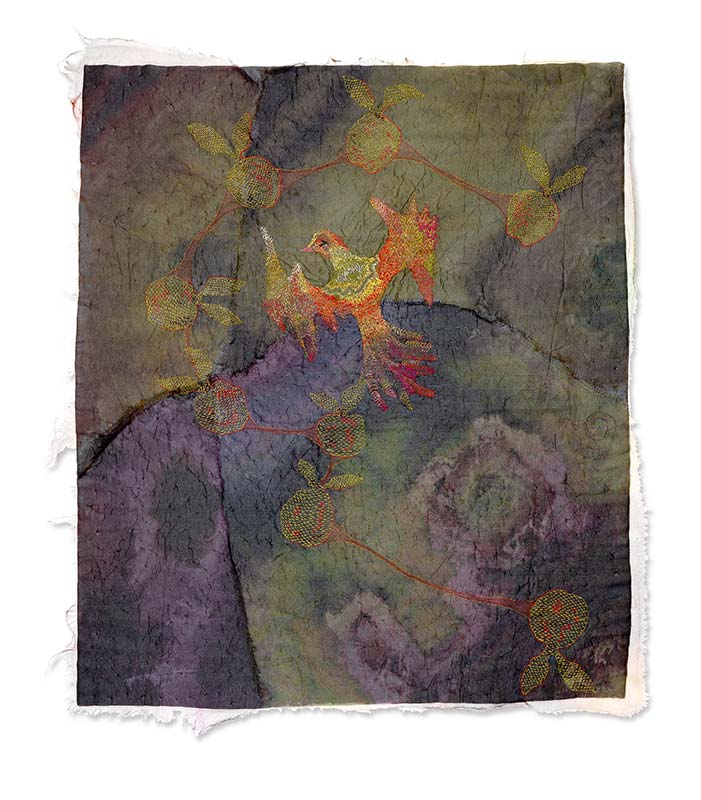

Some reflect her anguish at the suffering currently being inflicted on innocent civilians in Palestine, others are “just playing around”. When she finds a fabric that grabs her attention she might draw onto it first or simply start cutting shapes and placing them onto a background, then stitching them into place as vibrant raw-edge collages emerge, all bearing her organic signature logo.

A few weeks ago Marjorie shared her most recent works and again announced that these would be her last. When I smiled and chided her gently about familiar words, she was emphatic that this time she was done and I recognised finality in her tone.

Marjorie Colemen, pioneer of contemporary Australian quilt-making using our fauna and flora as inspiration, explorer of process and ideas, extraordinary stitcher, has parted company with her fabrics and threads. Her life’s work is done. We, her friends, are bereft but Marjorie herself is stoic.

What a prodigious legacy she leaves, far more than the sum of her nine decades of stitching. She has inspired generations of makers to be adventurous, to never stop exploring new possibilities, and to make work that speaks of their own place and life experience.

Thank you, my friend, for all you have done, and for all you are.

Post Script – Wendy Lugg

Contemplating pieces stitched by Marjorie Coleman in the two years since the 2020 publication of her major opus, Lyrical Stitch, which reviewed fifty years of her work.

Born in 1928 in Albany, Marjorie spent her early formative years on a farm in the biodiversity hotspot that is the south-western extremity of Australia, a place abundant with endemic flora pollinated by honey-eater birds rather than by insects. Home-schooled and without siblings, imagination became Marjorie’s constant companion. Playing alone in such a rich environment laid the foundations for the content of her adult artworks. The honey eaters, banksias and eucalypts first encountered in her childhood have been a recurring theme in works that have always reflected Marjorie’s life experience as an Australian living through the 20th century.

This small book documents Marjorie’s “Last Hurrah”, a collection of works made in 2021 and 2022 marking the completion of a lifetime’s magnificent body of work comprising more than two hundred stitched textiles. It represents the final chapter of a story comprehensively told on the website marjoriecoleman.com and in two previous publications. The first of these was the 2019 catalogue for the exhibition Following the Thread: Let the Cloth Speak, a survey of Marjorie’s work drawn mostly from the previous decade.

This was followed by the major opus MARJORIE COLEMAN — Lyrical Stitch, launched at Marjorie’s exhibition of the same name, held in 2020 at the Holmes à Court @ No. 10 gallery. This 192-page book is a visual delight, exquisite detail and colour leaping from every page. Artwork images are accompanied by a selection of Marjorie’s musings and poetry. There are essays giving insight into her life and work as well as a complete visual index of her artworks made over the previous 50 years.

In the two years since then, advancing age and failing health have restricted Marjorie’s activities. She has spent much of her time sitting and stitching, each new work started being pronounced her last. Yet then another would appear, and another. However, more than a dozen works later, Marjorie would have us believe that this time she has declared a halt. Drawing needle and thread through cloth has become prohibitively difficult. Her once-nimble fingers are increasingly stiff and unyielding, refusing to cooperate, making the fine work of earlier years no longer possible.

Physical frustrations aside, Marjorie has been content in this quiet occupation. Although she finds special joy in the wattle bird that visits her balcony each day, solitude is a comfortable companion. She claims to be a lifelong introvert who has learned to live among society, to fit in with a crowd, but who has always been most content in her own company.

These last works mark a transition, what she describes as a ‘softening’ from earlier robust ideas-driven stitched and written works that so often involved struggle in their birthing, a process she aptly described in the opening verse of her 1971 poem, Foreshadows.

It seems awkward creative style for nerve ends

to need ideas to urge them on, or damp them down,

and equally wry

that ideas must grasp substance in order to be declared;

thoughts are hard husbands to share with chemistry.

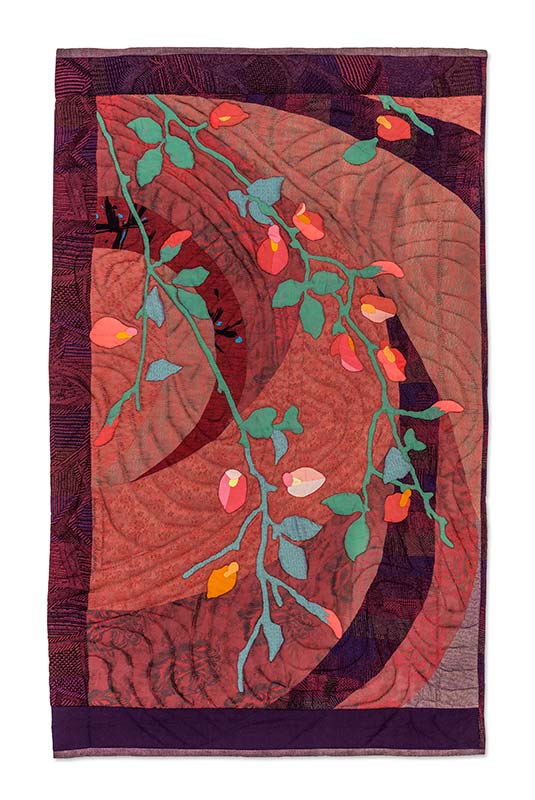

Whilst the “driving passions of many lives… the land, work, family and the notion of the sacred” are still present in her work, and several deal directly with the fragile state of the world, others are pleasurable collaborations with the cloth itself, her focus totally in the moment.

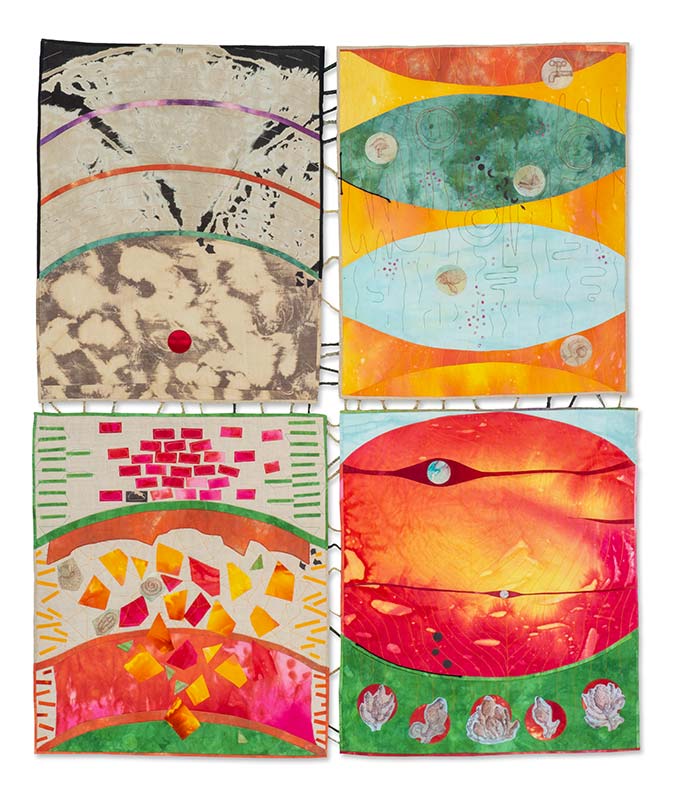

The three Menaces works were made with strong intent, clarified and refined prior to the first stitch being placed, each work reflecting a different menace to our environment. For instance, Quiet Menaces highlights the damage caused by the development of monoculture agriculture to meet the rising global demand for food. Not only is the escalation of this practice stripping the soil of nutrients, negatively impacting the microorganisms required for healthy balance, it is contributing to the devastating decline of our precious native flora.

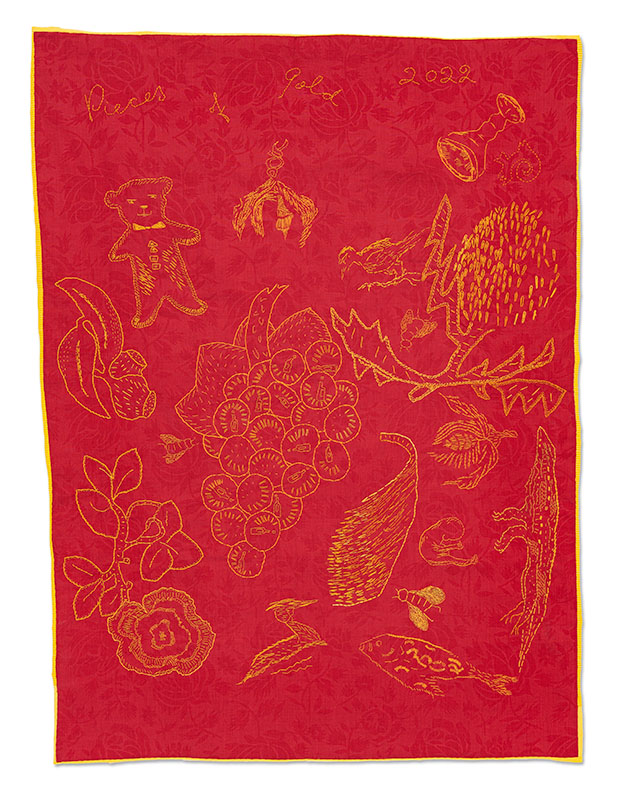

In contrast, Snorkel Time reflects upon decades of happy observation of the underwater world, both on trips abroad and during frequent encounters along shore-based coastal reefs only minutes from home. Pieces of Gold is a happy accumulation of experiences and interests, embodied in the form of various ‘treasures’.

Marjorie has allowed the final few works to carry her along on a collaborative voyage of discovery. In these pieces, she has worked developmentally, making a start then letting the work direct her. She is quite willing to be directed by the piece, rethinking and rearranging as the work progresses, her mind totally absorbed with the structure of the work. It might start off in one direction, then change its mind, directing her down a different path, sometimes right, sometimes not, requiring the retracing of steps, unpicking of stitches. And so with the titles of each new piece. These emerge as the work progresses. Sometimes the title just pops into Marjorie’s head, sometimes not, and sometimes it needs changing.

This means of working, whilst ostensibly not ideas-driven, is a fluid fusion of artist and cloth that demands a mind imbued with nimble flexibility. This agility can only come from decades of easy familiarity with and mastery of materials, process and ideas.

As Marjorie has so aptly stated -

The needle is my stylus, the thread my pigment

I like to express ideas… I can’t help it

2022

Quiet Menaces, 2021

60 x 110 cm, stranded cotton embroidery on silk

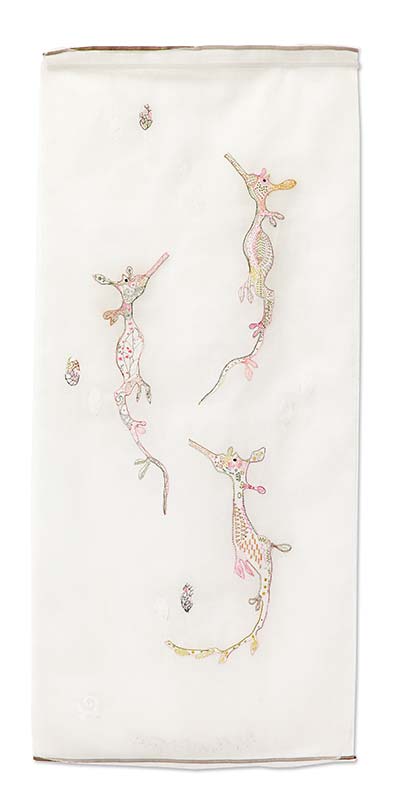

Snorkel Time, 2021

19 x 42 cm, embroidery thread with linen fabrics

Pieces of Gold, 2022

21 x 27 cm, embroidery thread on nylon fabric

Marjorie Coleman: Context for a Career – Grace Cochrane

Marjorie Coleman’s imaginative stitched textile works reflect an impressive accumulation of experiences and interests. She has been a significant contributor to the ‘contemporary’ or ‘studio’ crafts movement, which developed in many countries, including Australia, from the 1950s. It is fascinating to now investigate how she became involved and what has influenced her along the way. She graduated, for example, in 1949 with a Bachelor of Arts, Honours, in psychology, at the University of Western Australia, yet found her way to studying painting, drawing and textiles at the Claremont School of Art in 1974 – and hasn’t stopped since!

What was going on across this time? Around Australia, courses in art schools and technical colleges had increased in scope and number, postwar migration schemes brought in experts trained overseas, and many connections were made with those in the contemporary crafts world as it developed elsewhere. Australian craftspeople set up local, state and national membership organisations across all craft fields, through which they could correspond, meet and work together. Significant was the establishment of state (such as Arts WA) and national funding bodies, notably from 1973, the Australia Council for the Arts, which offered a range of grants through a number of boards including a Crafts Board, while the infrastructure of specialist dealer galleries, supportive philanthropists and museum and gallery collections also strengthened. There was a great deal of interest in establishing crafts centres as places of training and support, including the Fremantle Arts Centre in Western Australia in 1973, while education opportunities further expanded through TAFE colleges, colleges of advanced education and eventually universities.

Work in textiles evolved considerably during these decades; many artists increasingly used stitching and weaving techniques to not only create contemporary personal interpretations of familiar forms and functions, but also responded to changing ideas about art, craft and design through sometimes making sculptural forms and installations. From an initial involvement in quilt-making, Marjorie immersed herself in many of these opportunities, clearly interested in expanding her artistic horizons. Following a 1979 design course with Penny Whitchurch in Perth, for example, she carried out independent research at the Cooper-Hewitt Museum of Decorative Arts in New York and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. In Australia, she attended workshops with key people across the country, in a wide range of textile-oriented challenges including dyeing for embroidery with David Green, painted dolls and soft sculpture with Mirka Mora, quilting with Barbara Macey and Sonya Lee Barrington, surface design with Joan Schulze, machine appliqué with Marianne Spandjert, setting up suitcase exhibitions with Jan Irvine, experimental fibre with Heather Dorrough and a masterclass with Diana Wood Conroy. These have no doubt contributed to her current self-description as ‘stitcher of ideas’.

During these years, she also tutored in workshops and summer schools for Edith Cowan University, Albany Arts Council, the West Australian Quilters’ Association and the Embroiderers Guild of Western Australia, as well as for organisations in Melbourne, Tasmania, Sydney and Hawaii. She was one of four artists to oversee a community project to produce six large wall quilts for the Avon Valley Arts Society in Western Australia in 1993, and was invited to judge the members exhibition for the Australian Quilters Association in Melbourne in 1994. In 1995 her contribution to the field was acknowledged through her inclusion as an Elected Fellow of the Crafts Council of Western Australia (now FORM).

It is not surprising then, to discover the extent of Marjorie’s exhibition record. Earlier solo exhibitions include Discourse in 1991 and Timeline in 2006 at the Fremantle Arts Centre, and Following the Thread, Let the Cloth Speak, in Perth in 2019. From the late 1970s she has been well-represented in group exhibitions across Australia including the significant national touring exhibitions Quilts Across Australia in 1988 and Under the Southern Cross, to Australia, New Zealand, Europe and the UK in 2001–2003. She has also carried out some commissions, including a quilt representing the Perth region for the Bicentennial Authority in 1987, while her work is held in the National Gallery of Australia, the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney and the Holmes à Court Collection in Perth.

In bringing together a collection of her works from over 50 years, Marjorie Coleman – Lyrical Stitch not only demonstrates her innovative pursuit of ideas but also provides a wonderful record of a continuing professional commitment to textile art – and to Australia.

2020

Gumnut Blossom, 1980's

74 x 79 cm, cotton, machine stitch, raw edge appliqué.

Cat's Paw, 1980's

110 x 91 cm, cotton, hand appliqué, machine piecing

A Lifetime of Self Expression – Wendy Lugg

Marjorie Coleman has long been one of Australia’s most respected quiltmakers, acknowledged as a pioneer and leader in the field. By the 1970’s she was established as a national ground-breaker in the making of contemporary quilts with a strong Australian identity, featuring designs based on native flora and fauna.

Beyond the influence of her extraordinary body of work, Marjorie has contributed much time and energy to the advancement of the field. Many have benefitted from her teaching and from her involvement in the development of exhibition opportunities in formal gallery spaces. Always willing to offer an encouraging word, she has informally mentored many a younger maker.

However it is through her art that Marjorie speaks most powerfully. Her textile works are the product of a sharp intellect, astute observation, and empathy with her subject matter. They invariably exhibit fine craftmanship, but this is subjugated to their purpose as a means of self-expression.

As a young woman with an arts degree and honours in psychology, Marjorie found voice for her feelings in poetry, potent musings on matters of personal import – family relationships, theological mysteries and the beauty of familiar flora and fauna. Then she found a new voice in stitched cloth and the poetry ceased, no longer necessary.

Many decades later Marjorie is still finding new means to give voice to her ideas. She describes all her works as explorations, with a constant tension between discovering new, often unconventional, materials and processes whilst submerging these into what the piece is saying.

“I want to master technique and then forget it. When it is the how of the piece that first draws attention rather than the what, I feel that the piece is disappointing and will eventually pall.”

Latterly her interest has turned from the quilt medium to the predominant use of stitch, sometimes as line, sometimes as blocks of colour, but always following her personal narrative.

“I fancy that the stitch stands as something like the alphabet: not existing in its own right unless and until it serves the greater purpose of conveying something beyond itself.”

Now in her nineties, Marjorie continues to produce new work, stitching for her own enlightenment, with a strength and vigour that belies her age.

“I regard myself a stitcher of ideas. To work on an idea in whatever medium is fulfilling and even exciting; there is no space for boredom or unhappiness.”

These late works, largely stitched on linen or silk organza, are restrained, often delicate and sometimes ethereal. They are introspective, drawing on a lifetime of experiences and ideas and reflecting Marjorie’s passion for the bush and the underwater world. The same Australian native plants and birds that appeared in her early work are still present. There are also the sea creatures, such as the weedy sea dragons, familiar to Marjorie from her many years of snorkelling among them.

One work might ruminate on the inhabitants of a limestone wall passed on a ramble, another might explore the habits of water birds observed over the seasons at nearby Lake Monger. Bush birds might join Marjorie in searching for the Tree of Life.

What remains constant is Marjorie’s intention to reflect her life as a contemporary Australian, living in this place at this time.

2020

The Gifting: Fire, Rock, Water, Seed, 2003

128 x 104 cm, hand dyed and bleached cotton, synthetic, drawing, machine appliqué, fused raw edge appliqué.

Fashionista, 2012–13

112 x 53 cm, silk chiffon, hand stitching.

Stitching Alive – Belinda von Mengersen

Sit;

look down, slow,

to the draw of a hand-pulled thread,

drawn down, along.

The broken line.

To see Marjorie Coleman’s work is to be reminded of many things: the wondrous light-filled opening sequence of Jane Campion’s Keats biopic ‘Bright Star’, with sweeping close-ups and the exquisite sound of a needle drawing thread through cloth; time spent in the presence of the Lady and the Unicorn Tapestries. For this is what art does: it reminds us – bringing us back into relation with other exquisite moments in time, allowing us – momentarily, the joy of reliving them.

Coleman stitches a language in threads drawn from her mind, marking out memory, experience, intuition, and joy. Her drawn motifs are wrought onto translucent cloth sheaves. Fine thread marks are built into barely fashioned forms and laid onto textured territories. It is as if sheet-after-sheet of silk organza – starched by its retained sericin – and already rich with stitches, has been tenderly pulled from the wax tablet of her mind. Colours develop as dots of light flicker and flit, shifting along with the cloth, seemingly suspended and only momentarily caught. Like a fleeting moment of light captured photographically – slightly out of focus – equally, enervating and evanescent. The embroidered animal, plant, and human motifs in Coleman’s work somehow both absorb and transmit light, refractions from threads illuminating the way forward. A quest, in Colemans work, reminiscent of “À mon seul désir” in the Lady and the Unicorn Tapestries. This series of tapestries depicts five senses – taste, hearing, sight, smell and touch through scenes of plants and animals along with an elusive sixth sense, a profound desire for love, where “À mon seul désir” portrays will, desire and yearning. Why else is stitching wrought over again, in a slow intimate unraveling? The pace of the unfurling narrative is akin to a slow accumulation of stitches; and hand stitch is ever bound by an antiquated duration. Coleman’s quest-like approach to her studio practice is equally evident in her pursuit of influence and comparison through workshop classes and personal museum-based study. She has carefully distilled a knowledge of stitch structures into her own dialect, influenced but not dictated to by traditional quilt-stitching methods like Kantha, and running stitches for bonding layers of cloth together. This distillation has resulted in a purity of method, defined by sets of simple stitches that interpret and illustrate – lifted apart from the need to quilt and, instead, determined upon the need to narrate.

Although rendered from deeply personal experiences along the continuum of her own life, Coleman’s stitching and its insatiable quest for expression is understood more fully when placed in the context of the evolution of contemporary stitch practice in Australia during the 20th century, inspired by stitch artists from the United Kingdom. Constance Howard, through her teaching at Goldsmiths College, University of London (1947–1975), and her international lecturer tours and prolific publications on stitch was, albeit indirectly, one of those influences. Howard’s well-documented shifting of the concept of stitch, from pattern-based ‘embroidery’ to fluid and imaginative ‘drawing’ – elevated drawing and decreed that stitch was drawing with thread. Tellingly, Howard, like Coleman was trained in drawing as a visual artist first, and this philosophical difference can be clearly seen in her legacy, through the primacy of drawing, and the ability of artists like Coleman, to use embroidery as a tool for drawing. Howard’s personal challenge was to shift the perception of stitch from pattern to drawing. Crucially moving contemporary stitch practice away from guild-influenced rule-following and precision, to independent stitch ‘interpretation’. Stitching veered away from the formal application of a strict, predetermined method to a language open to interpretation. Coleman’s link to Howard was David Green (1940-), who was taught by Howard at Goldsmiths and in-turn traveled to Australia to run workshops, then returned permanently to teach (1978–2010). According to those influenced by him, there is no ‘softly-softly’ approach to stitch with Green; he advocates original interpretation. Thus, it can be seen that subversive practice models confer the courage to listen more closely to one’s inner voice: and it is the intimacy of such listening which compels us as viewers of Coleman’s work.

Coleman’s practice as a deliberate pursuit of influence and comparison, demonstrates a quest-like seeking fueled by an ever-attentive curiosity. Coleman’s thoughtful work is illuminated by deep emotional intelligence and the universal metaphors within her personal stories. As Jane Hirshfield reminds us, “perhaps for something to be found, the only thing that matters is that there be searching” [or stitching].

So, sit.

Look down.

Think.

Stitch.

Return.

To read full essay go to:

https://www.academia.edu/43401982/Stitching_Alive_The_work_of_Marjorie_Coleman

2020

We all Carry Baggage, 1999

150 x 51 cm, mixed media, plant dyes, hand and machine stitching

Yilgarn Postman, 1987

112 x 70 cm, cotton brocade, rayon, machine piece, hand needle-sweep appliqué, hand quilting.

Following the Thread – Wendy Lugg

Marjorie Coleman has long been one of Australia’s most respected quiltmakers, acknowledged as a pioneer and leader in the field. By the 1970’s she was established as a national ground-breaker in the making of contemporary quilts with a strong Australian identity, featuring designs based on native flora and fauna.

Beyond the influence of her extraordinary body of work, Marjorie has contributed much time and energy to the advancement of the field. Many have benefitted from her teaching and from her involvement in the development of exhibition opportunities in formal gallery spaces. Always willing to offer an encouraging word, she has informally mentored many a younger maker.

However it is through her art that Marjorie speaks most powerfully. Her textile works are the product of a sharp intellect, astute observation, and empathy with her subject matter. They invariably exhibit fine craftmanship, but this is subjugated to their purpose as a means of self-expression.

Over the years Marjorie has explored many unconventional materials and processes. She describes all her works as explorations, with a constant tension between discovering new processes whilst submerging these into what the piece is saying.

“I want to master technique and then forget it. When it is the how of the piece that first draws attention rather than the what, I feel that the piece is disappointing and will eventually pall.”

After many decades of arts practice, Marjorie is still finding new means to give voice to her ideas, but latterly her interest has turned from the quilt medium to the predominant use of stitch, sometimes as line, sometimes as blocks of colour, but always following her personal narrative.

“I fancy that the stitch stands as something like the alphabet: not existing in its own right unless and until it serves the greater purpose of conveying something beyond itself.”

Now in her nineties, Marjorie exhibits less often but has continued to produce new work with a strength and vigour that belies her age. This exhibition draws from a prodigious body of work made in the last decade, which she describes as having been stitched for her own enlightenment.

“I regard myself a stitcher of ideas. To work on an idea in whatever medium is fulfilling and even exciting; there is no space for boredom or unhappiness.”

These recent works, largely stitched on linen or silk organza, are restrained, often delicate and sometimes ethereal. They are introspective, drawing on a lifetime of experiences and ideas and reflecting Marjorie’s passion for the bush and the underwater world.

The same Australian native plants and birds that appeared in her early work are still present. There are also the sea creatures, such as the weedy sea dragons, familiar to Marjorie from her many years of snorkelling among them.

One work might ruminate on the inhabitants of a limestone wall passed on a ramble, another might explore the habits of water birds observed over the seasons at nearby Lake Monger. Bush birds might join Marjorie in searching for the Tree of Life.

What remains constant is Marjorie’s intention to reflect her life as a contemporary Australian, living in this place at this time.

2019

The Search for the Tree of Life: #10

Here, There, Where, 2009

98 x 83 cm, synthetic, embroidery threads, hand stitching.

The Search for the Tree of Life: #6

In the Mirror, 2008

91 x 58 cm, silk, various fabrics, cotton threads, hand stitching.

MARJORIE COLEMAN 2025